PETER COPENHAVER

Vice President, Ishpeming Ski Club

Ishpeming, MI

vp@ishskiclub.com

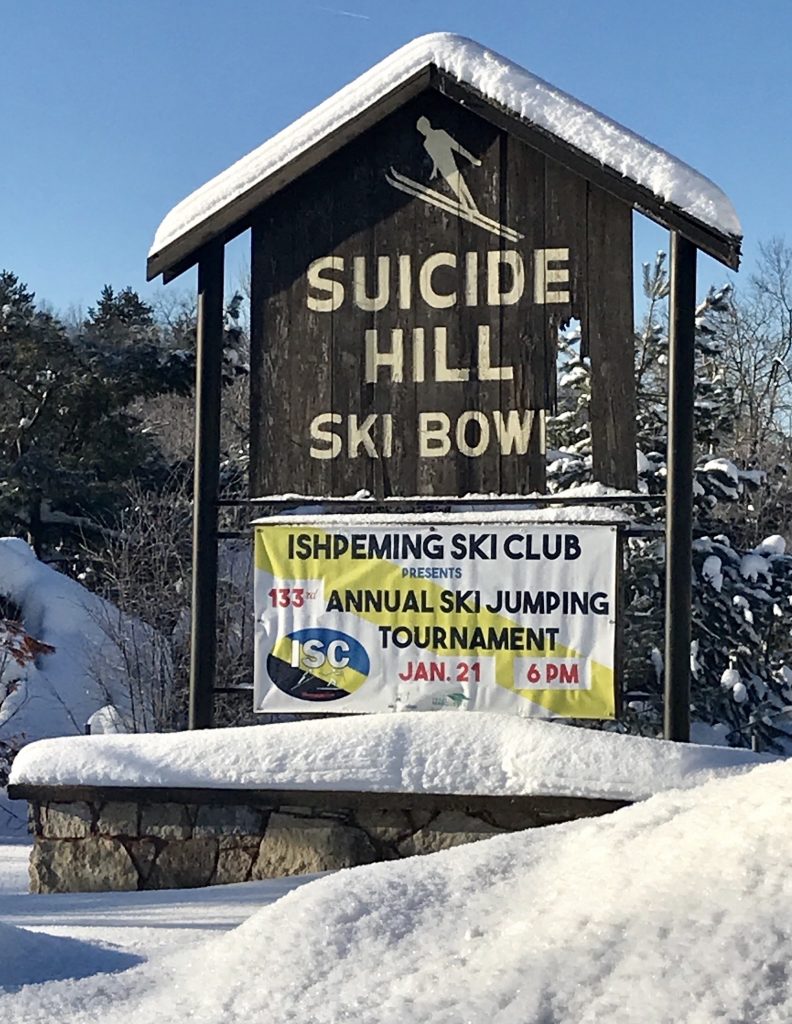

Suicide Hill at 100: A Century Carved in Ice and Iron

“Kids built their own hills. That’s about all we did all winter.

We started as soon as the snow came and kept it up until spring.”

— Jack Bietila, ISC ski jumping legend

When you stand at the base of Suicide Hill on a winter night, you can feel the cold falling down the knoll long before the wind hits your face. Floodlights cut through the dark. Wind makes the inrun tower hum above the trees. And somewhere beyond the quiet, you can almost hear it — a century of skis on track, a hundred winters of breath held as jumpers leapt forward into the void.

This winter, Suicide Hill turns one hundred years old. A hundred years of flight, fear, courage, and community. But the story of this hill begins even earlier — with a town and a ski club shaped by snow and speed.

Ishpeming is widely recognized as the birthplace of organized skiing in the United States. Nordic immigrants brought their skis to the Marquette Iron Range in the late 1800s, and by 1887, they had formed what was then the Norden Ski Club, hosting their first tournament in 1888. That club became the Ishpeming Ski Club, which has held a ski jumping tournament every single year since, through world wars, depressions, and pandemics. The ISC has never missed one.

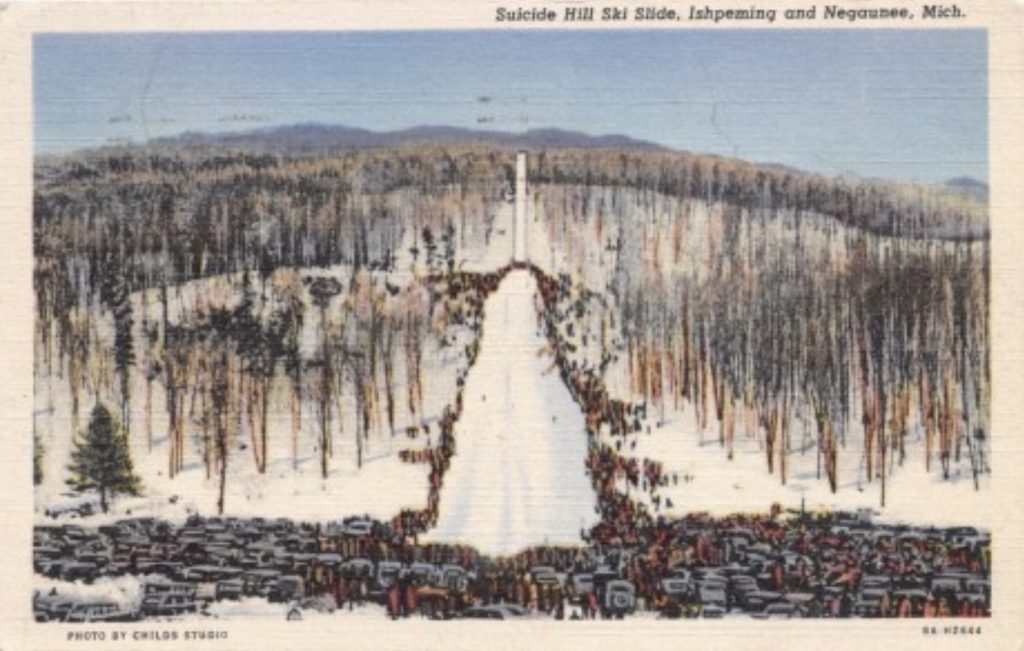

Between Ishpeming and Negaunee lies a narrow valley — a natural winter amphitheater. One side carried long, rolling cross-country terrain; the other offered the steep, clean pitch needed for a big jump. Early ski club members recognized it instantly. Here, they decided, was the future.

On October 1, 1925, the City of Ishpeming leased the land from the Cleveland-Cliffs Iron Company, and ISC members went to work. Miners, ironworkers, carpenters, and millworkers — the same men who toiled all day underground or in the mills — spent their nights and weekends building a world-class ski jump with nothing but hand tools, grit, and a willingness to climb high steel in the winter wind. The hill rose fast. On February 16, 1926, local jumper Walter Anderson made the first practice jump, landing around 110 feet. Others followed, pushing farther with each run. The hill was big. It was fast. It stood as a testament to what could be built when vision, labor, and belief came together. On February 26, 1926, nearly 5,000 spectators crowded into what had become known as Suicide Bowl for the first official tournament. Families walked in from the train station. Cars filled the ski bowl. And the new hill came to life.

That first winter, the slide had no official name. Local reporter Ted Butler began calling it “Suicide Hill,” even after club members asked him not to. The name stuck because it reflected the truth: the hill inspired awe and respect in equal measure. By the 1930s, the Iron Ore newspaper was writing that the slide was “known far and wide as Suicide Hill,” and while no fatalities had occurred, “thrills, spills, and narrow escapes” were part of the experience. Ski jumping here wasn’t a spectacle. It was a risk taken by real people in a real community. Around here, that wasn’t nostalgia. It was normal. Kids built hills because winter invited it. That same instinct — to climb something high and see how far you can fly — is what eventually built Suicide Hill.

Jack Bietila’s childhood memory captures the essence of ski jumping in Ishpeming perfectly:

“Kids built their own hills. That’s about all we did all winter.

We started as soon as the snow came and kept it up until spring.”

— Jack Bietila, ISC ski jumping legend

From the beginning, Suicide Hill was a community project. The land came from Cleveland-Cliffs. The City of Ishpeming backed it. Local businesses donated supplies. The National Guard brought equipment. Construction companies lent bulldozers and loaders. The Kiwanis Club, Rotary, Lions, Jaycees, Sea Scouts, and countless others raised money, ran concessions, staffed parking, and organized banquets. Volunteers shoveled snow up the landing in 55-gallon drums, stomped it firm with boots and skis, and shaped the outrun by hand. They staffed every role: Hill Chief, starters, judges, medical crews, announcers, and the teams who maintained the scaffold.

The hill was rebuilt again and again: an improved landing in 1941; major expansion before the 1951 North American Championships; Olympic tryouts in 1960 and 1963, where Gene Kotlarek flew 251 feet before crowds of 7,000–10,000; and a complete steel rebuild in 1972, engineered by Earl Langsford and led by volunteers including Dave Holli, using hand winches and raw ingenuity. Later projects, including Operation Big Push in 1978, expanded parking and access as crowds grew.

SUNTRAC improvements in the 1980s, largely overseen by landing hill engineer Don Liljequist, reshaped the landing to meet evolving FIS standards, ensuring that Suicide Hill remained modern, safe, and competitive while preserving its soul. Through every decade, one truth remained: whenever the hill needed work, the community showed up. Suicide Hill has never been just a structure — it’s a forge.

The Bietila family alone shaped an era: a ski jumping family from Ishpeming — Anselm, Walter, Jack, Ralph, Paul, Leonard, and Roy — who soared off Suicide Hill and into American ski jumping history. Crowds came as much to watch the Flying Bietila Brothers as to see the official standings.

Other local legends — Rudy Maki, Robert “Butch” Wedin, Dick Raho, Willie Erickson, and many more — turned Suicide Hill into a launchpad for national and international careers. After World War II, foreign skiers from Norway and Sweden came to test themselves here, adding global flavor to a deeply local tradition.

A decade ago, the ISC transformed from a club of aging jumpers into a youth-centered Nordic institution, teaching cross-country skiing, ski jumping, and Nordic combined. We rebuilt the pipeline from the K13 to the K90. We reinvested in coaching, year-round training, and partnership programs. Today, we see athletes like Timothy Ziegler, a Nordic combined skier who grew up soaring off Suicide Hill and is now pursuing graduate studies at Northern Michigan University. Isaac Larson, a senior at Negaunee High School, is training and competing nationally and internationally, carrying the discipline and technical mastery of the modern jumper. Kaija Copenhaver, a junior at Marquette Senior High School, first clicked into tiny jumping skis at age five and now travels across the country and abroad to compete — still returning to Suicide Hill, her home ski jump.

This year, Suicide Hill will host its 139th Annual Ski Jumping Tournament — 139 consecutive years, without a miss. For nearly all of that time, Suicide Hill has stood as the heart of the event. This hill was built and rebuilt by miners, carpenters, ironworkers, and volunteers who gave their nights and weekends to a dream of flight. It has been sustained by families, supported by local businesses, and carried forward by generations who believed winter could build strength and character. Because Suicide Hill didn’t just survive a century. It earned one. And it’s already reaching for its next.

You can also Venmo this year! To donate, find us at @usaskijumping

Or send a check to:

USA Ski Jumping

PO Box 982331

Park City, UT 84098