HALEY & WILLIE ERICKSON

Iron Mountain, MI

herickson@usaskijumping.com

Of all the ways people know my grandpa, most start with his name and a list of accomplishments. Olympian. World Cup champion. Entrepreneur. A time when American ski jumping was still carving its place on the world stage. I think of a grandpa whose life quietly set the course for my own. He is the reason ski jumping feels like home, the reason cold air and towering inruns feel familiar instead of intimidating, and the reason this sport is stitched so deeply into my life.

I grew up in the shadow of the jump. Not just the physical structure of Giant Pine rising above Iron Mountain, but the legacy that came with it. My earliest memories are shaped by stories passed down, quiet lessons, and the unspoken understanding that ski jumping is as much about courage and humility as it is about distance and medals. My grandpa’s legacy isn’t something I learned from history books, it was woven into everyday moments and carried on through stories, values, and a deep respect for the sport. This is my view from the landing, a reflection on the man behind the medals, and how his courage in the air still echoes through USA Ski Jumping, my family, and my life.

Most stories of his begin with something completely random, something my sister and I will be talking about, and it reminds him of a ski jumping memory. He seems to be able to tie just about anything to it. He’s not the kind of man who sits there for hours and talks about his days in ski jumping, though he absolutely could. He offers more tidbits that lead from one thing to the next until we forget where we originally started. We can only get small amounts from him from time to time, but here are a few memories he was able to talk about.

Today started with a FaceTime call with my mom while I was visiting my grandpa, and we were standing in front of his trophy case, one that looks like it holds enough awards for an entire team. As we moved slowly from shelf to shelf, he stopped at a photograph of four men posed outside of a small plane and said, “I was just showing Haley and telling her a little story about this picture right here… four guys from one ski club made the team. The four of us from Iron Mountain. Myself, Jim House, Dick Rahoi, and Rudy Maki. That was our first trip to Europe.” He laughed as he explained that back then, their jumping skis were so long they had to be laid down the middle aisle of the plane because they wouldn’t fit underneath with the luggage.

We moved on to a painting commissioned for him by Ted Tavonatti from the 1958 World Championships in Lahti, Finland – a moment frozen in time. That painting later hung in the bar he owned with my grandma, Willie’s Olympic Lounge, where stories like these lived on the walls as much as they did in conversation. He told me how, after retirement, he and Rudy Maki made it a tradition to return to Lahti for every World Championship. “Rudy and I were at the Seurahuone in 1978,” he said, “and we’re standing in the lobby when we see a big trophy case with a picture advertising the ’78 World Championships.” They went to the front desk and told the manager they had something to show him, that they had been there in 1958. The hotel staff took a photo of them standing proudly in front of the advertisement, delighted that two jumpers had come full circle. They repeated that pilgrimage every winter for as long as I can remember, until age finally made the journey too difficult.

He has a trophy case full of hardware, and somehow he can still tell you exactly where he was standing, who he was competing against, and how the air felt the day he earned each piece. When I asked him which one mattered most, he didn’t hesitate, but he didn’t reach for the biggest trophy either. Instead, he pulled out a small medal attached to a faded red, white, and blue ribbon.

“The Norge Ski Club was perhaps the most premier club in the country,” he told me, turning the medal over in his hands. “They always brought in foreign skiers; the best in the world came to Chicago.” The Chicago Medal of Honor was awarded to the best jumper in that competition, and in 1957, that jumper was him. He laughs now when he talks about it, calling himself “just a young sh*t… 18 years old,” but that year meant everything. He won ten competitions, captured national titles, and solidified himself as one of the best ski jumpers in the country. He remembers staying at the Palmer House, standing in front of the president of the ski club as the medal was placed around his neck. He points to a photograph of that moment and then to the medal itself. “There are some things you never forget,” he says. Shoutout to Norge!

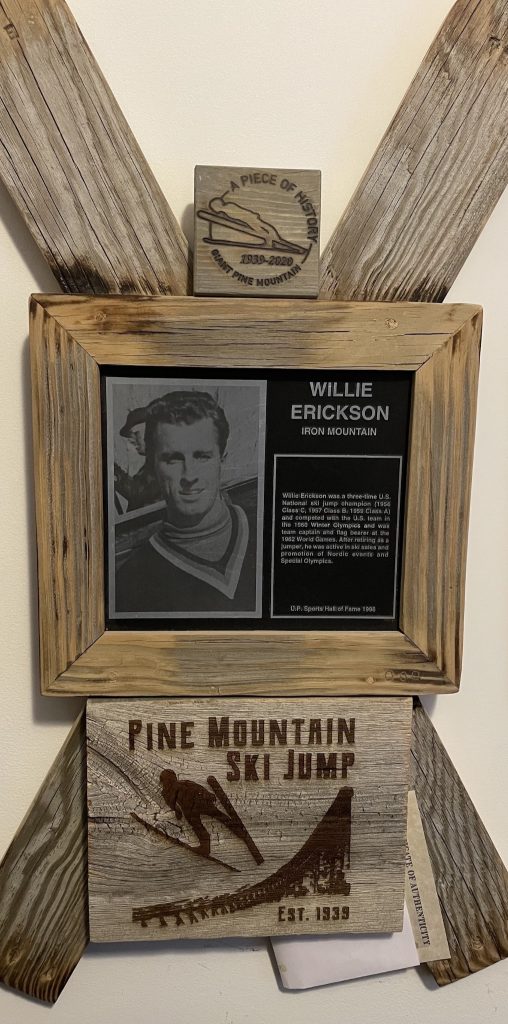

Ski jumping was never the only thing my grandpa was good at. At Northern Michigan University, he was a football player during the school’s best season ever, held the U.P. record in track for the long jump, and earned the nickname “The Flying Flivver with Jack Rabbit Legs.” But even with success in team sports, he chose ski jumping. He liked that it was individual. The accountability. No one else to blame. No one else to thank. Just you and the hill. That mindset carried him to become a three-time U.S. National Champion – first as a junior, then as a Class A/B champion in the late 1950s, and eventually onto the 1960 U.S. Olympic team in Squaw Valley, California.

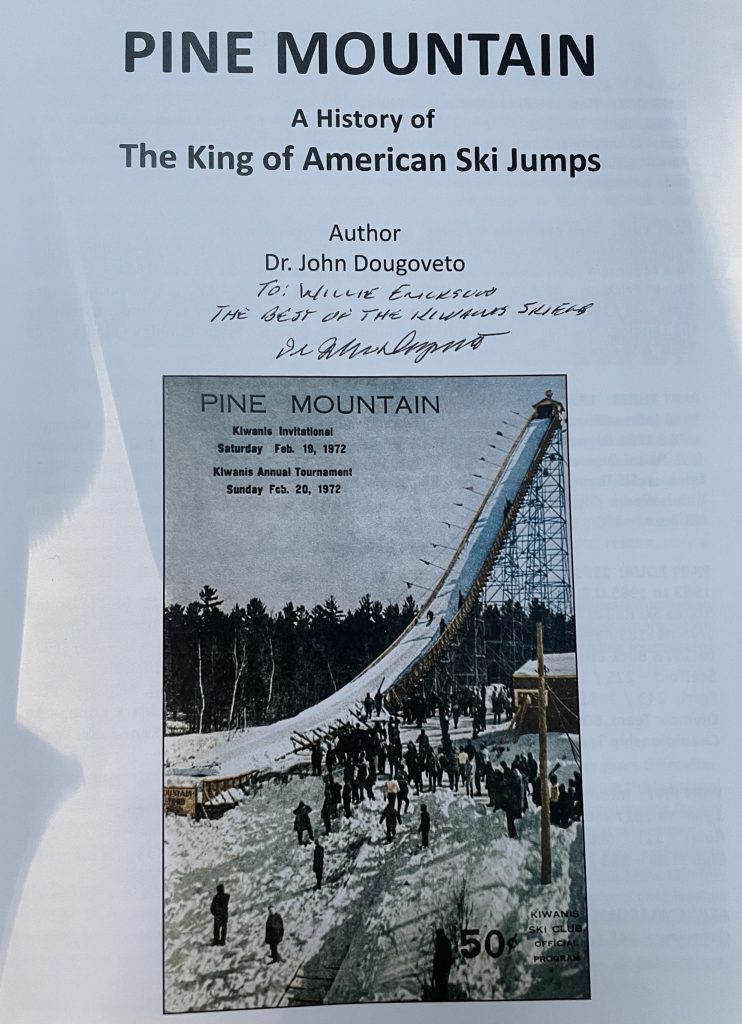

That sense of independence took root early in Iron Mountain, where he was born and raised in a community defined by ski jumping. With Pine Mountain looming above town and the Kiwanis Ski Club at the heart of it all, jumping wasn’t just a sport; it was a way of life for kids, and every neighborhood had its own little jump. As a kid, he even appeared in early newsreel footage of American ski jumping, already part of the fabric of the sport before he fully understood what it would become. In the 1940s, foreign ski jumpers would come to town and visit schools, and young Willie was captivated – not just by how far they flew, but by the idea of ski jumping as a one-man show. “You either did, or you didn’t,” he said.

His first skis weren’t store-bought. His father, a Finnish immigrant, made them by hand – boiling wood to bend the tips, hanging them in the basement rafters with weight on the tails until they took shape. Hickory and maple. Bindings made from rubber backstraps cut out of old inner tubes. That Finnish-American heritage, shared by so many ski jumpers in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, shaped both his upbringing and his approach to the sport. Later, figures like Fritz Tschannen, a Swiss ski jumper who competed in the 1948 Olympics, would come to his elementary school, playing the accordion and telling stories about ski jumping, making the world beyond Iron Mountain feel closer than it was.

As he grew, he sought out the best places to train. He spent time at the Ishpeming Ski Club because, as he put it, “that’s where all the good ones were – Coy Hill, Paul Bietila, all those guys.” He wanted to be around greatness, to let it rub off on him, to be inspired by it. That instinct carried him beyond the U.S. to international competition at the FIS World Championships in Lahti, Finland, in 1958 and Zakopane, Poland, in 1962, as well as ski flying events across Europe. While training with the U.S. team in Finland in 1962, he met Maija, who would become his wife and partner for the next 59 years.

To the world, Willie Erickson is a business man and one of the most prominent American ski jumpers of the 1950s and 1960s. After his competitive career, he returned home and used his name and love for the sport to build a life in Iron Mountain – owning a restaurant, opening a ski sales and rental shop, and continuing to give back to the community that shaped him. Even decades later, he remains a local icon, a storyteller, and a keeper of ski jumping’s history, often appearing alongside other legends to share memories from what he calls the “poetry in the sky days.”

To me, he is more than a résumé or a record book entry. His legacy isn’t just measured in medals or distance – it lives in the stories he tells, the values he passed down, and the generations shaped by the courage it takes to stand at the edge of the hill, look down, and choose to go anyway.